Starting with iron ore from Western Australia and coal from Queensland, the very steel that forms the shell of Hyundai cars made in its 17 plants around the world has Aussie origins.

We learn this fact while staring at a huge stack of gunmetal-grey rolls of steel sheet, each weighing several tonnes, in a storage area of Hyundai Motor Manufacturing’s European car manufacturing plant at Nosovice, in a far flung corner of the Czech Republic.

Czech this: Hyundai’s European factory in the Czech Republic can turn out 350,000 cars a year, with some bound for Australia.

We are here to learn about the car manufacturing process in the plant that provides most of Hyundai Motor Australia’s Tucson SUVs, along with i30 and ix20 hatchbacks for Europe, at the rate of 66 cars an hour or 350,000 a year.

Rather than the usual factory tour inflicted on motoring writers, this one is different: a hands-on experience over two full days, working briefly on the cars at various points in the production process to get a better understanding of how the system works.

And these are real cars heading for customers around the world. One of them, a Tucson Active that is about to be born at our hands (sort of), will be delivered all the way to Melbourne for us to test drive, so it better be right.

Of course, we are being watched, coached and assisted by senior workers at each station on the line. When things go pear-shaped – and they do – the experts step in to take over to ensure no customer gets a car with a part bolted on upside down.

Having been given our safety drill and fitted out with steel-capped shoes, safety glasses and work pants that would do a hip-hop artist proud, we start at the beginning: the press shop.

It is here we note the rolls of steel that are, apparently, made in South Korea by Hyundai Steel, a subsidiary of Hyundai Motor. The rolls are brought to the factory by ship and train and stored until needed in the press shop, which is the next stop for us.

Here we are shown the big multi-tonne steel dies that, under 5400 tonnes of pressure in massive presses, shape the sheet into panels. We are told these dies need some TLC to keep them ship-shape, and that includes polishing every now and again.

We are handed an electric polisher and, after a quick demonstration, set to work buffing a die. We note, however, that they have asked us to buff the outside edges of the die, not the bit that actually stamps the panel.

When panels are stamped, every 20th piece is checked, and so that’s what we do next – rub a door frame with an abrasive strip to highlight any imperfections. Right on cue, a series of door frames with an incomplete laser weld drop in front of us, to the embarrassment of press shop operators. It seems the machine that butt-welds thin steel with a thicker sheet has a headache today.

But this is why this check station is included in the car-building process, to make sure these defective parts are picked up and corrected before they enter the assembly process.

From here, the panels are moved to the welding shop where more than 300 robots wave their arms, bringing together the panels in a shower of sparks to form the bare-steel body.

Up to eight different models can be handled by this automated process – one of the most human-free parts of the construction.

We help out to form a door which is then fitted with three others to the car before it disappears into the paint shop.

Painting these Hyundai cars is the most time-consuming part of the manufacturing process, taking nine hours for robots to apply various sealants and paint coats, with each coat dried in an oven to speed the hardening process.

Because the paint area needs to be clean as a hospital operating theatre, right down to dust-resistant anti-static suits worn by the handful of operators allowed in there, we bypass this section and jump to the assembly area where half of the plant’s 3300 employees toil on a passing parade of now-brightly coloured, shiny car bodies.

The first job is to remove the doors to facilitate easy access to the cabin for fitting the dash assembly, seats and other interior goodies. The doors travel down a separate line and, if by magic, reappear later in the process in the correct order to be married up again.

To aid the assembly process, large sections of the mechanicals are assembled off of the production line, in modules. One such module involves the whole powertrain – the engine, transmission and drive shafts – along with the entire suspension system, brakes and even the fuel tank and fuels lines – lifted by machine from beneath the car into place where it can then be bolted tight.

With dozens of powertrain and chassis combinations available for various Hyundai models made on this line, co-ordination of parts and assembly of such modules and their place in the process is both staggeringly complicated and ultra-crucial to ensure the correct bits meet up with the correct body, just as the customer ordered.

Theoretically, the plant could build a staggering 90,000 combinations, but it keeps it to a manageable 3500.

Once again, computers control the process to keep all the balls in the air.

We are again brought into the fray, helping to bolt front door stays onto a series of cars. Armed with a rattle gun, we fumble the first few (and watch as the line workers fix them).

We are just getting the hang of it when we suddenly discover that while the Tucsons we have been working on have bolts, the i30 that suddenly appears has nuts to be fixed – a new process that throws us out.

This is just a warm up for the next process that involves bolting the entire front module – radiator assembly, bumper, grille and assorted other bits – to the car. Lifted into place by a line worker using a mechanised lifter to take the weight, we launch into action with a rattle gun and a handful of bolts, a line worker pointing to each bolt hole that needs to be filled with steel – about six in all on our side of the car.

Compared with our other efforts, this station proves the most successful, despite its comparative complexity and importance.

Not so the next one, where we are asked to fit the chrome-plated badges onto the rear hatches of the cars, according to a mysterious order that we cannot quickly fathom.

After a couple of aborted attempts, we let the experts take over to prevent a badge being fixed sideways or on the bumper instead of the boot.

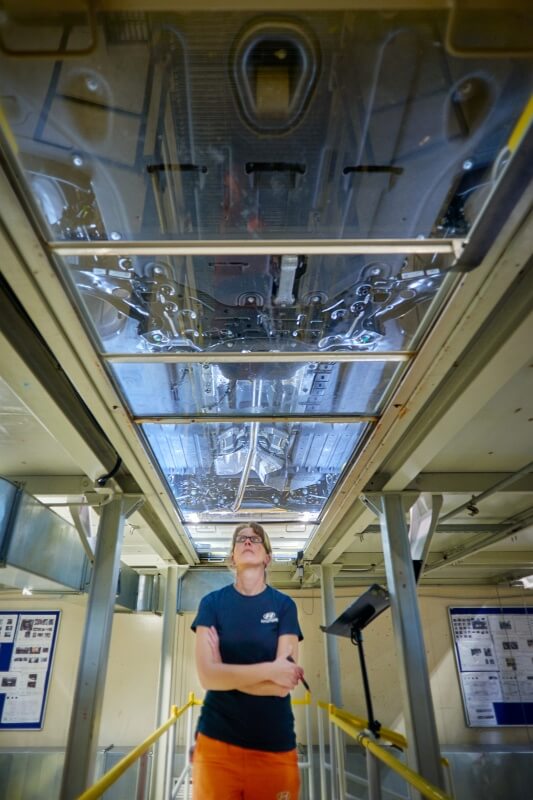

After about 20 hours in the production process, the cars near the end of the line where they are fuelled – just enough to cover the testing and delivery process – and checked.

Experienced gloved hands go over the paintwork under bright lights, checking for flaws, and then all the functions are checked in a systematic process that even includes a twist of the rear vision mirror to make sure if can be adjusted satisfactorily.

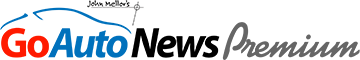

The engine and transmission are tested on a “rolling road” dynamometer, and then a test driver takes the wheel for a real, comprehensive drive around a road course, complete with bumps to detect rattles and an inspection pit where the driver leaps out to look for any leaks on the underside.

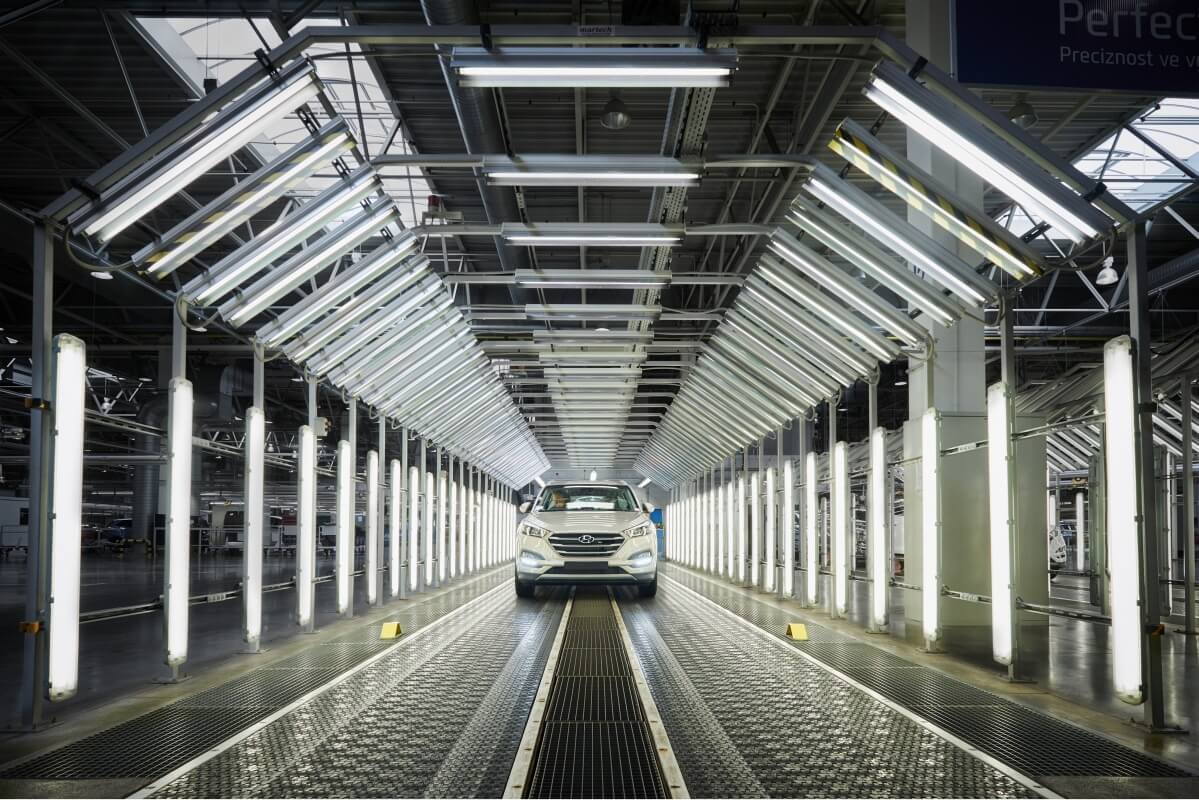

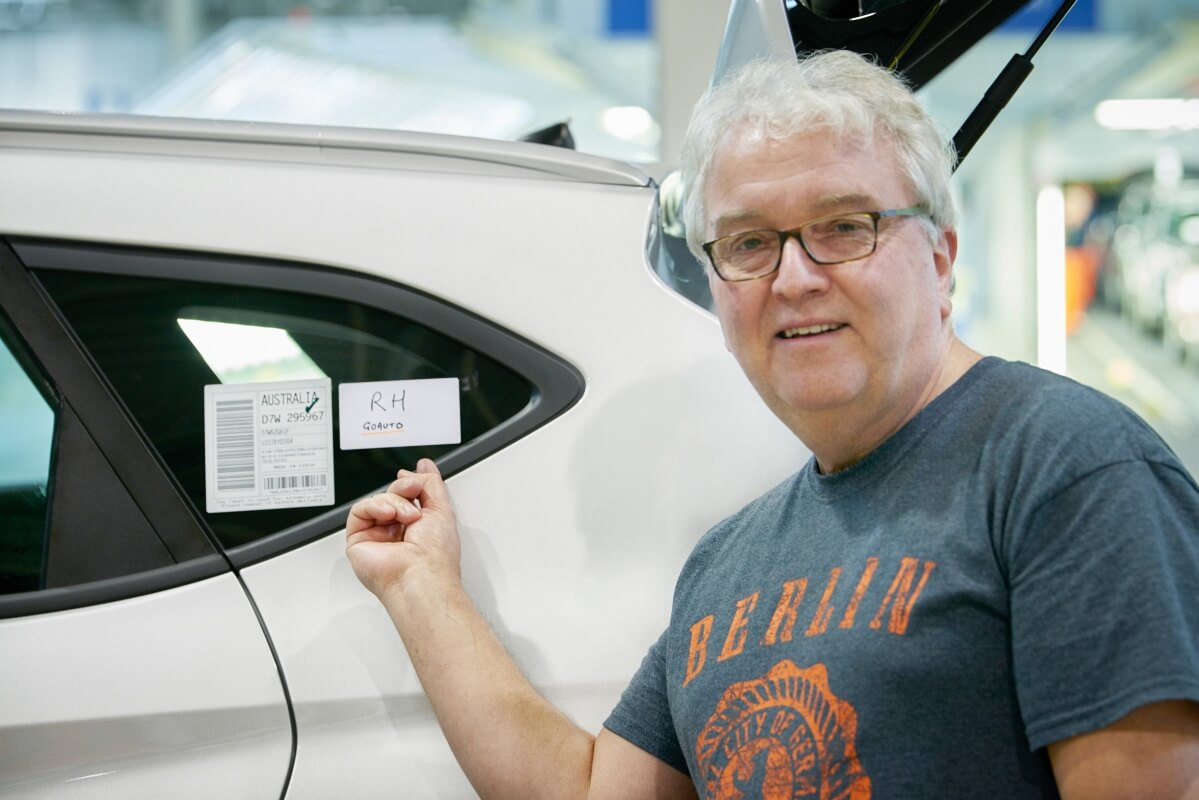

Finally, the car gets the tick of approval for shipment, but not before we attach a couple of stickers to “our” Tucson to help us confirm its identity on delivery to Melbourne where we will get to drive it.

It is then parked with hundreds of others in a storage car-park next to a train siding for loading on daily double-decker freight trains bound for northern ports on the Baltic Sea for loading onto the ships.

Having left the assembly line on September 27, our Tucson was loaded aboard the good ship Glovis Courage in October to begin the long voyage to Australia where it travelled via Durban and Singapore to arrive in Melbourne in mid December.

Then, at a dealership pre-delivery centre at Essendon, in Melbourne’s north-western suburbs, we catch up with the vehicle again, noting that our identification stickers – one on the rear quarter glass and another inside the spare wheel rim – are still firmly in place.

Then we help to complete the production process by stripping off the protective shipping plastic on the exterior panels and seats and then, in a symbolic final flourish, screw on the number plates.

Three months after it was born, we are handed the keys and the vehicle is delivered into our hands, just in time for Christmas. Sadly, it has to be returned in the New Year.

You could hardly say we built the car, but nevertheless, we couldn’t help feeling a certain ownership as we slipped behind the wheel.

By Ron Hammerton

Read More: Related articles

Read More: Related articles