As the separate article in this issue points out, the international community is searching for answers to a complex problem that threatens total loss of cargoes, total loss of ships and with used EVs in all different states of repair increasingly finding their way into car ferries that also carry passengers, there is an increasing danger to the public as well.

The London-based international law firm, Watson Farley & Williams, which, amongst other things, specialises in the transport industry, has released a thoughtful paper which outlines the risk that EVs pose in transit (mainly at sea), the possible remedies and the responsibility of the various parties to the shipping of these cars.

The paper, prepared by David Handley and Mike Phillips, contains such valuable insights into the problem that GoAutoNews Premium has published it here in full for the benefit of our readers:

THE ISSUE

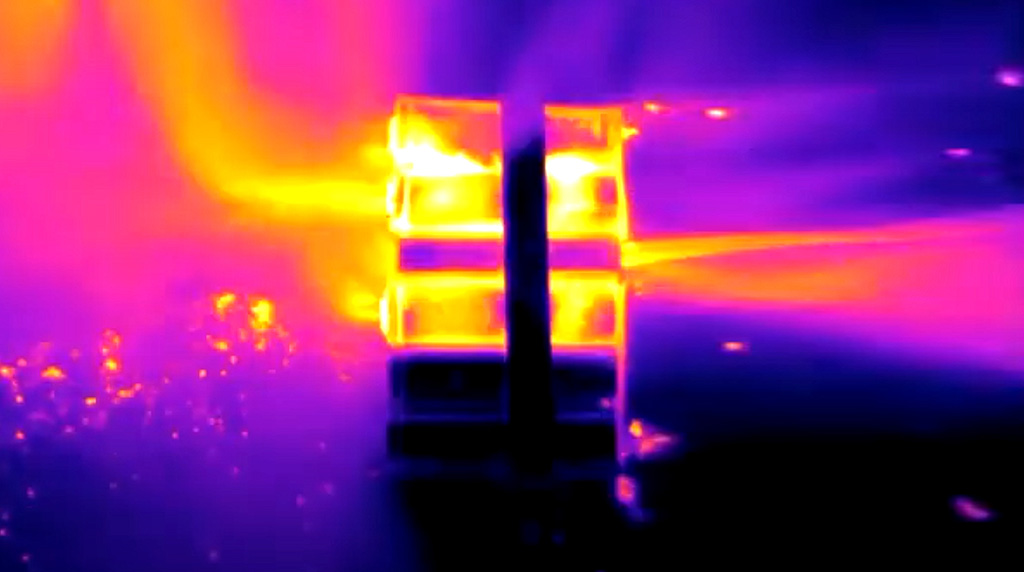

In normal operation, EVs might not seem to be any more inherently dangerous than their ICE cousins. The world’s firefighting services, however, are finding that may not be the case when one of these vehicles catches fire. The component materials of the batteries mean that the fires are very energetic and traditional firefighting techniques do not necessarily work. This will differentiate the risk of EVs from ICE cars when carried on board ships.

The component materials of the batteries mean that the fires are very energetic and traditional firefighting techniques do not necessarily work.

Statistically, the estimated failure rate (and therefore risk of combustion) of an individual battery cell is one in 10 million. However, when you consider that an average EV contains approximately 7000 cells, the risk increases significantly.

Data from the London Fire Brigade suggests an incident rate of 0.04 per cent for ICE car fires, but the rate for EVs is more than double that at 0.1 per cent. Although it is not clear whether EVs are more likely than ICE vehicles to catch fire, it is common ground that the consequences are potentially more disastrous and more difficult to handle.

This is not just an issue for the vehicle carriage trade. With an increased use of EVs, ferry companies will see greater numbers carried on their fleets. This may represent an even higher risk, given that the vehicles will be a variety of ages and in a variety of charge states.

This is not just an issue for the vehicle carriage trade. With an increased use of EVs, ferry companies will see greater numbers carried on their fleets.

Additionally, in a competitive market, ferry operators may offer charging points onboard to ensure electric vehicles are fully charged for their onward journeys.

LIABILITY FOR EVS AS CARGO

Most standard shipping documents prohibit the shipment of undeclared dangerous goods: a shipper must give notice of the dangers to the carrier so that they are able to take suitable precautions to ensure the goods can be carried without causing damage; to itself, the vessel or other cargo.

If a declaration is not made and those goods go on to cause damage, the shipper is liable for the loss caused. This has been seen regularly in the container trade with the carriage of Calcium Hypochlorite.

There is, therefore, a distinction between ICE and EVs when considering them as classes of cargo.

ICE vehicles are carried with the minimum amount of fuel to reduce the risks as much as possible. ICE vehicles are, therefore, for all intents and purposes, inert machines.

The component that carries the fire risk in an EV cannot be removed; the battery cannot be drained of electrolyte. An EV has chemical components that, in the right circumstances, can initiate and sustain a fire; often a very energetic fire.

In addition, ‘normal’ firefighting techniques are less effective in fighting EV fires. Two common suggestions are either to let the vehicle burn out or submerse it in water. Neither is likely to be appropriate in the confines of a ship.

Two common suggestions are either to let the vehicle burn out or submerse it in water. Neither is likely to be appropriate in the confines of a ship.

There is a further complication in that most of the firefighting water used ashore is freshwater. At sea the fire main is pressurised with seawater, which may have consequences given that it is significantly better at conducting electricity than freshwater.

Another issue with fighting these fires is the gases that are released. The smoke from a lithium-ion battery can be equally as dangerous as the fire itself. Ashore, this can be vented to the open and so will pose much less of a risk than it does on an enclosed vehicle deck.

The smoke from a Li-Ion battery can be equally as dangerous as the fire itself.

Before a crew member can attempt to tackle a fire in an EV they must don a specialist gas tight suit, which is much more difficult than a fire suit and SCBA (self-contained breathing apparatus). The delay in response time will be significant in a situation where the general consensus is that early response is the best response.

The onus is not all on the shipper. If the carrier has accepted the cargo, knowing that they are EVs or has held themselves out to be experienced in and capable of carrying EVs, they must fulfil that bargain.

If a fire breaks out and the crew has failed to employ the appropriate firefighting techniques because of lack of training or equipment, the carrier may well be liable to the cargo owners and will not be able to rely on fire exemptions in their shipping document.

Another possibility is that the fire may be caused by a manufacturing defect in the battery itself or the car had been damaged on loading.

New systems will need to be devised and incorporated into ship design.

It may be difficult to determine the precise cause, but if it was established that the damage to the battery that led to the fire had occurred on loading, the stevedoring company may find themselves involved in complex claims involving large sums of money.

FIGHTING AN EV FIRE

If crews are not aware that fighting an EV fire requires a different technique to that employed in fighting a conventional fire onboard, it is easy to see how an incident could lead to a total loss.

The evidence indicates that current suppression and drenching systems will not be sufficient for this new risk. New systems will need to be devised and incorporated into ship design.

A high-fog system fitted at deck level may be a long-term solution. However, its effectiveness would need to be considered against the maintenance requirements to keep it operational and it is unlikely to be viable in the short term as a retrofit.

Other solutions may involve labelling and loading best practice so that crews can easily identify an electrical fire early on and use the appropriate methods. And spotting any overheating using thermal cameras would allow deployment of cooling mechanisms to prevent it developing into a fire.

The carriage of increasing numbers of EVs will undoubtedly require a change to procedures and shipping documents… it requires engagement and collaboration from all stakeholders.

NEXT STEPS?

The carriage of increasing numbers of EVs will undoubtedly require a change to procedures and shipping documents. This is not a problem that any one part of the supply chain can solve, and it requires engagement and collaboration from all stakeholders.

Shippers must ensure that they provide the information that vessels need to make sure safe carriage is possible.

They will need to tell the carriers when EVs are being carried, as opposed to ICE vehicles, so that stowage can be planned accordingly. Where EV and ICE models are impossible to distinguish visually, that might include some physical mark which makes it easy for the loading officers to tell which vehicles are which.

Carriers will need to ensure that their contracts of carriage allocate risk and correctly identify categories of cargo. EVs which are unidentified should be rejected.

Carriers should also ensure that their vessels are properly equipped, which includes carrying the correct fire fighting appliances and ensuring the crew is trained to tackle the fires. That may mean sending crews on specialist courses or developing specialist courses as an essential part of their training.

EVs which are unidentified should be rejected.

It may be that a certain state of charging of the battery significantly mitigates the risk and OEMs may wish to consider a carriage mode that ensures the battery is in the safest state possible. It is likely early detection will be key. OEMs may be able to assist by developing a way of plugging the vehicles into a monitoring system utilising the batteries’ internal sensors.

It is likely early detection will be key.

Regulators will need to look at the current regulations to determine if they are adequate to deal with this altered risk. Alterations to SOLAS (The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea) are likely to be required in the long term.

However, in the short term, regulators and operators should work together to ensure that risks are mitigated in a way that is appropriate and manageable. This can only be carried out effectively if it is part of a collaborative process.

Insurers and particularly those in the cargo market should be aware of the altered risk and help to ensure that shippers are doing what they can to minimise the risk. This may require a special EV clause in the policy, be that cargo or hull.

P&I clubs (protection and indemnity insurers), through their loss prevention departments, should continue their excellent work so far to bring the issue to the attention of the industry.

Salvors (salvage operators) should be consulted and their experience utilised to help understand how they might tackle a fire should one occur. To consider what to do once a fire is already alight would seem too late.

Allocation of risk in contracts should be a risk prevention tool, rather than a reaction to a catastrophe.

In the ferry trade, operators should look at whether it is possible to check battery health before carriage and whether EV owners should be required to provide evidence of compliance with minimum standards.

At the very least, EV owners should declare that they are bringing an EV on board.

At the very least, EV owners should declare that they are bringing an EV on board. Terms and conditions should also be updated to ensure that the altered risks of carrying EVs are taken into account and passengers are aware of any obligations, such as charge condition.

CONCLUSION

Whilst the carriage of EVs is likely to be no more inherently dangerous than the carriage of ICE vehicles, the dangers they pose are different and the consequences potentially more severe.

Stakeholders should ensure that those dangers are discussed and mitigated, and the changed risk profile contractually allocated. Allocation of risk in contracts should be a risk prevention tool, rather than a reaction to a catastrophe.

Read more: EV fires become hot issue

Read more: EV fires loom large

By John Mellor

Read More: Related articles

Read More: Related articles